Available Works

Biography

born in são paulo_ brazil_ 1983_ lives and works in são paulo

Chaim develops a practice that moves across drawing, photography, video, installations and performative actions, understanding drawing not as the preparation of an idea but as the vestige of a body in action, an inscription that emerges from the encounter between gesture, space and materiality. The body, always present and active, enters a direct relation with the supports and the recording devices, producing marks that do not aim to represent but rather to attest to the event of the action itself. Her visual language is guided by a precise reduction of elements, a distillation that allows the essential aspects of the gesture to surface and its traces to become material for thought. Moving between performance, expanded drawing and technical imagery, Chaim investigates the mediality of the body and the ways it inscribes itself in the world, making the trace not a residue but the very mode of existence of her work.

Carla Chaim holds an MFA in Visual Arts from the Escola de Comunicação e Artes (ECA), University of São Paulo (USP). She graduated in Fine Arts from Fundação Armando Álvares Penteado (FAAP) in 2004 and completed a postgraduate degree in Art History in 2007. In 2025, she is presenting her solo exhibition Suspensión at MACBA in Buenos Aires and participating in the group show Mulheres – Proposals from Brazil at Artnexus Space in Miami. Earlier in 2025, she took part in artist residencies at El Espacio 23 in Miami and Appleton in Lisbon. Among her recent solo exhibitions are: Risco at Appleton, Lisbon (2025); Dobrar Cartas, Riscar Jornais at Quase Galeria, Porto (2023); and Febre at Galeria Raquel Arnaud, São Paulo (2021). In 2020, she created the arena/stage installation for the performance project Histórias da Dança at MASP, São Paulo, when her work was acquired for the museum’s collection. In 2016, Chaim was nominated for the Future Generation Art Prize and, in 2017, exhibited at the Pinchuk Art Centre (Kiev, Ukraine) and at Palazzo Contarini Polignac (Venice, Italy), as part of a collateral event of the Venice Biennale. Her work has been featured in group exhibitions such as: Quase a Noite, Espaço das Artes, São Paulo (2025); A Vingança do Arquivo, Casa de Cultura do Parque, São Paulo (2024); Paving Roads for Latin American Art, Coral Gables Museum, Florida (2023); This is big big big, This is small small small, Osnova Gallery, Moscow (2021); 1981–2021 Brazilian Contemporary Art, CCBB, Rio de Janeiro (2021); Descategorized – Artists from Brazil, Fundación ArtNexus, Bogotá (2020); Frucht & Faulheit, Lothringer13 Halle, Munich (2017); Ichariba Chode, Plaza North Gallery, Saitama (2015); and Impulse, Reason, Sense, Conflict, CIFO, Miami (2014). Chaim received the EFG Latin America Art Award in 2022. In Brazil, she has been awarded the CCBB Contemporâneo, FOCO Bradesco Prize (both in Rio de Janeiro), as well as the Funarte Award for Contemporary Art and the Energias na Arte Award, both in São Paulo. Her work is part of collections including Ella Fontanals-Cisneros (Miami, USA), Museu de Arte de São Paulo – MASP, Museu de Arte do Rio – MAR, and Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo, among others.

Exhibitions

“… toda palavra sã”

05 feb - 28 mar_ 2026

afinidades- raquel arnaud 40 anos

mar 19 - may 04_2014

carla chaim- weigh the weight

nov 26 - dec 20_2014

Texts

Bruno Moreschi interviews Carla Chaim

text published in the catalogue of the exhibition Carla Chaim, Julia Kater, Marcia de Moraes: Um de Três, Prêmio FUNARTE de Arte Contemporânea, SP, BR, 2011

Bruno Moreschi: Carla, when did you start to take interest in art and decided to become an artist?

Carla Chaim: Since I was little I’ve gone to museums and galleries with my parents. They are interested in arts, music, and general culture – my father is a musician. In trips we would always go to museums, and I remember going with them to the Bienal de São Paulo. When I was only 4 years old I started attending art classes, where I drew with colored pencil, and I still have these initial works. Later, when I was 9, I made oil paintings and these painting classes went on until I was 17. They were pretty traditional canvases, very colorful, filled with flowers… Then I started graduation in Fine Art at Fundação Armando Álvares Penteado, in São Paulo. I also majored in Art History in the same institution.

During graduation I was faced with other less traditional techniques, and really came to know what was this “contemporary art”. It was during this period that I started studing Art History further and understanding some issues that didn’t even cross my mind before. In summary, with these new discoveries, I found out that I could do much more than just paint. The interesting thing was that I really loosened up: during graduation, with every new exercise I explored a different theme and I wasn’t worried if I was making ‘art’ or not. This experimentation, without fear of making mistakes, remains within my work until now.

Bruno Moreschi: How was it to have become aware of this broader art field?

Carla Chaim: I learned that we must make art, but we must also think. That’s why I think I’ve completely abandoned those colorful canvases I used to make when I was younger. Works such as those didn’t interest me anymore within the poetics and discourse that began to arise during graduation. I changed completely: from painting I went to sculpture. My final graduation work was an installation with three steel sculptures, and I was oriented by Professor/Artist José Spagniol. It was then that I realized that color no longer interested me and that I needed to start developing a more complex thinking. But this didn’t come as an obligation; I found it enjoyable to work like this, researching subjects and materials.

Bruno Moreschi: In other words, you began to realize that art is also thinking…

Carla Chaim: Exactly. To me, art is thinking. I don’t think this is true to everyone, but I do see the need to always have a concept tied to it. Hence I quote Duchamp, when he said that the artist thinks above anything else. However, I must make it clear that I don’t defend thinking before doing. I’m talking about reflecting upon what you are doing. When I’m working I don’t bother formalizing the work, I don’t think about fitting it into an aesthetic of ‘beauty’, nothing like that. I don’t even care how it will turn out, if it’ll turn out ugly, beautiful, full, empty, black or white. What really interests me at this point is a wider poetics that encompasses processes, concepts that permeate the beginning and the end of a work.

Bruno Moreschi: It’s curious that you say this. Once the artist Regina Silveira told me that a lot of young people showed up at her studio stating that they wanted to train

their hand for drawing. Before these youngsters she would reply that what you must train is the mind, not the hand.

Carla Chaim: I agree with her. When you start a drawing and think about it, you have a stronger confrontation with the paper and with everything that relates to you in that moment.

When you want to just make, put it out, paint with emotion, paint red because it’s the color of blood, blue because it’s the color of the sky, it turns out so sentimental that it doesn’t interest me. I like the works that make the spectator think, that raise doubts.

Bruno Moreschi: What do you think of this, let’s say, trend of the contemporary artist to become more and more a kind of a planner? In other words, to think art as a project. Do you see that in your work too?

Carla Chaim: I myself create my projects, like “little rules” for me to work. But I think there will come a time when I’ll be able to pass this responsibility on to other more qualified people. The artist has this freedom today. He doesn’t need to be an expert in the fields that he works in. If he wants a porcelain sculpture, he has someone more experienced to do it. A figurative oil paint, another person can paint, a huge steel sculpture too…

Bruno Moreschi: What was your first work where this idea of a more “thought of” art appeared?

Carla Chaim: It was the video I presented at Centro Cultural São Paulo, in 2008. This work (Movimento Singular do Verde para seu Complementar no Tempo Desaparecido [Singular Movement from Green to its Complementary in the Disappeared Time], 2008) was made in a time when I didn’t have a studio. When I was without a studio, I ended up seeing myself with only the 38-square meter apartment I was living in. I didn’t even have a table to work on. To solve this problem, I bought graph A4 paper and several oil sticks. Before these materials I just needed to decide what to draw. I had made many figurative things, and observation drawing didn’t interest me anymore, so I didn’t want to draw what was in front of me. I wanted to draw, but something different than that. So, it hit me: what if, instead of using my hands, which are already conditioned to drawing, I tied the oil sticks to my arms?

Bruno Moreschi: This way you remove the easiness of drawing, right?

Carla Chaim: Yes, and it satisfied my need for new challenges. I thought it extremely important to not have control.

Bruno Moreschi: Or establish a new kind of control…

Carla Chaim: Certainly. To try to create rules to block the traditional way of drawing. And, therefore, also test myself. This was a work that I found had something there that I could explore further, which is how the body works. By the time of those drawings, I was majoring in Art History, I used to read a lot of Walter Benjamin and other names of the School of Frankfurt. My supervising teacher was my Aesthetics Professor, so I dove into this subject and started to realize, while reading Benjamin, that the modern society body begins to be articulated in another way. So, I wanted to test these body limits of today; the physical body and also inside a social limitation. I wanted to talk politics, but at the same time make drawings.

Bruno Moreschi: Once I heard you explain something interesting about the recording of your performances. You mentioned that your interest wasn’t to make well- produced videos, but to register that moment in the most direct way possible. Is video really a recording means in your work?

Carla Chaim: In these videos where I record myself drawing, yes. The super-produced video needs a team. It’s something else. I like working in partnership. But to have a team to develop works, I don’t think I’m there yet. I want to arrive at the studio and make. When I need to turn the camera on many times, put on makeup, create a set, I fall into something that is not instinctive, it’s not spontaneous. It’s like I become an actress, and this doesn’t work for me. It’s like all spontaneity of the work gets lost.

Bruno Moreschi: I think your work may even become produced videos, but at the moment it’s not what you want…

Carla Chaim: The moment now is for drawing, so much that I learned to edit videos just so I wouldn’t depend on anyone else. To me, video is placing a camera on a tripod and recording myself while I draw. It’s basic, simple, but records exactly the moment, my body, and the way I produce drawings. It’s in fact a registration of the process, which is the part that interests me the most. In some cases, the final drawing may not even interest me as much.

Bruno Moreschi: I think your work has something very much in common with a lot of not so traditional contemporary artists like the ones who just paint, draw, etc., which is the fact that contemporary artists possess new skills to make art. And these skills are not great ones. It’s like every work required from the artist a partial skill, but as soon as another idea appears, this skill is put aside and a new process begins with the use of new procedures. Do you see your work this way?

Carla Chaim: Yes, I do. Every work requires a way to be made, a place, a how. I like to discover how a certain work can function in a certain way. My studio is in fact an assorted research lab.

Bruno Moreschi: And how is this research process to you? How does it come to be? Does it start from a text, something more theoretical, or from the experimentation of a material itself?

Carla Chaim: I read a lot. The texts fill my mind with thoughts and my notebook with notes. But I also try to look at the world around me. I think our day-to-day mundane things are very good for us to think about. It’s like these things were isolated from the ordinary environment. The works in the series Natureza Molhada [Wet Nature] (2009) deal exactly with what I’m talking about. I grabbed a rolled up paper and dipped it into a tube with water and paint. The interesting thing is the large scale: it’s a paper roll of 4 meters. The result ended up being a landscape with a horizon made from the difference between black and white. All this from a simple action of dipping paper into a tube with paint.

Bruno Moreschi: It’s a kind of active observation before the world, right? The work is not only a repetitive practice made inside a studio.

Carla Chaim: Yes, it’s walking on the street and stumbling on an idea, let’s say. When you have this work routine, you can’t distance yourself, close the door of the mind, of the studio, and go home think about other things. It’s like I produce 24 hours a day. An example: one day I went out to buy some paper and I saw at the store a bunch of strips of balsa wood, and I thought about making a video in which I bended

this wood until it snapped. The result of this was the work Risco de Uma Vantagem Cíclica [The Risk of a Cyclic Advantage] (2010). In other words, it came from a ‘stumble’. And it was not because I was at an arts and crafts store, but because I was alert.

Bruno Moreschi: An artistic attitude before the world?

Carla Chaim: I think it’s a greater attention before it. This is my way of thinking, of stimulating a creative process. When I did the artistic residency in Banff, in Canada, I wasn’t allowed to use anything toxic. No solvents, no nothing. So I started using water-based paint. Actually I didn’t have any specific project to develop in this residency. I went with the intention of finding something that interested me there. On the second day of residency, I walked into a toy store and bought several things; among them, a toy that makes soap bubbles. When I arrived at the studio, I mixed the soap bubbles with paint. This resulted in a large series. This is why I say my studio is a kind of a lab. I spent almost a year working with these bubbles, studying ways to compose it. On white paper it becomes something more related to Biology, cells and molecules that are walking on the paper. Then, I made it on black paper and the result was more related to the universe, black holes (series Exercício para Construção e Fixação do Infinito [Exercises for the Construction and Fixation of Infinity], 2010). In a third phase, I only made parallel lines. This made the bubbles look like music scores (series Composições [Compositions], 2010). It’s curious to realize that, as with the drawings I made tying oil sticks to my arms, in this case I’m also drawing with my body. Here with an extension of it, the blow.

Bruno Moreschi: This issue of the body is present in a lot of your works, sometimes directly, other times indirectly. Are you the kind of person who is very aware of the movements and limitations of your body?

Carla Chaim: I’d attended dance classes. My engravings in college were dancing scenes. I don’t dance anymore, but I’m still aware of my body, of how it can move, which are the limitations, how it balances, its functions, articulations…

Bruno Moreschi: It’s a study of the body, but perhaps of a part of the body that doesn’t have as much technique and mastery? I mean, when you make drawings in which you don’t use only hands, which are skilled for drawing, but you use your arms, you’re sabotaging yourself and trying something else that is not skill.

Carla Chaim: It’s not about skill anymore, but about an understanding of an articulation.

Bruno Moreschi: And it’s a gesture that is not usual to be made. Are you interested in these unpredictable movements of the body?

Carla Chaim: Very much. And it interests me so much because I think the body is able to speak in different ways, as if I’m revealing a hidden body, unknown. One of my works was precisely about balance, which, in a way, reveals this other body. I stood on top of two bases and made a circuit walking from one to the other without stepping on the floor. (Sabendo Assim do Tempo de seus dezembros [Thus Knowing About the Time of your Decembers], 2008). This generated difficulty to me and a test to my body.

Bruno Moreschi: And a new way of moving, right?

Carla Chaim: Sure. You must be very secure in a place to be able to walk to another. And it works as a life metaphor too. I like making simple works and letting themselves unfold at every new relation with whoever sees them.

Bruno Moreschi: Does a work like this demand a lot of training?

Carla Chaim: None at all. The first time it was perfect, I didn’t fall. When I tried to do it again, I fell. That’s why I used the first try. I think it worked the first time because I was very concentrated then. There’s also a naivety when you try something for the first time. In all my videos I think for a long time about how to make it, I make sketches of how it would work, I raise possibilities like they were projects of an action. But usually I use the first tries, because I like the unpredictable.

Bruno Moreschi: Which was the work that physically demanded the most from you? Carla Chaim: I’m not interested in the extreme limitations of the body. Although that first video I told you about, the one with the drawings made with the arms, demanded a lot because that movement caused pain. In order to make two good videos I made many others, so my back ached. And to make matters worse, I always forget to stretch beforehand. Even so I don’t usually take my body to the limit of exhaustion. This just doesn’t interest me now.

Bruno Moreschi: It’s impossible not to notice that above you, on the wall, there’s a poster of the artist Rebecca Horn. Is she an artist that interests you? What are your influences?

Carla Chaim: I find her work amazing. I really like the artists from the 60s and 70s.

Bruno Moreschi: And for what reason? Is it their experimentation that catches your attention?

Carla Chaim: Body experimentation, actually. I’m very conscious of references. I like having references. They are things that feed me too. Among Brazilians, I really like Cildo Meireles, who has a perfect conceptual closure. With regard to the body, I’m interested in the 1960s and 1970s artists. Like this phase of Rebecca Horn, Bruce Nauman, Carolee Schemann, and many others. From this drawing perspective, I like Brice Marden, Sol Le Witt, Richard Serra, who has some amazing drawings, an easiness, a weight. I’m interested in the drawing that is treated viscerally, honestly. When there’s respect for the material being used.

Bruno Moreschi: Respect for the material? How so?

Carla Chaim: It’s you letting the material be what it really is. I had a teacher, Charles Watson, who showed us a video once of Brice Marden talking about how the drawing needed to become like a shield, so strong and so striking. And I relate to that. That’s why I like oil sticks.

Bruno Moreschi: This respect for the material actually relates to several works from Richard Serra…

Carla Chaim: I recently saw an exhibition of his in New York. I’d like to have done everything I saw there! It’s even hard to accept that he did so many good things. I like to talk about my references because today an artist can’t be naïve anymore and pretend he’ll be a lone creator. I act like someone who transforms and who talks to the present and to the past.

Bruno Moreschi: Tell me a little bit about your work called Laboratório de Desenho [Drawing Lab].

Carla Chaim: That work (Laboratório de Desenho / Experiências Extrassensoriais Específicas [Drawing Lab / Specific Extrasensory Experiences], 2009) was made from cardio exams I really had to do. When I was doing the exercise test, I noticed the little pen drawing by my side. Instantly I thought, “I’m drawing with my body without ever touching the paper! I’m jogging and the signals are being captured by the electrodes and being passed on to the paper, thus making a drawing.”

I kept the exams and wondered how I could use them in my work. Then, I decided to present drawings made with different exercise test machines while I did different actions, such as treadmill, apnea, eating…

Besides that, I filmed myself making these actions with the machines. I made simple non-figurative videos, like, for instance, I was riding a bike and filmed only the shadow of the wheel. After several drawings I selected those that interested me the most. Then, I made a steel cubic structure, because I was interested in placing the spectator inside a new body. There was a projector that kept exhibiting an image on the floor and all these little screens with speakers that kept on producing visual information and different sounds to the spectator. My intention was in fact to transport the spectator to another place. There were also headphones in the center of this cube, where you could hear the beating of my heart. If people closed their eyes they’d have the feeling of being inside my body.

Bruno Moreschi: Once again a drawing that wasn’t made by hands.

Carla Chaim: Exactly. And it was very enjoyable working with elements outside the studio, with Medicine in this case. I was able to use this technology because I have a friend who’s a Cardiologist. By the way, when he saw my work I heard something very interesting from him: “After seeing your drawings, whenever I get people to take echocardiograms I no longer ask them to take the exam, but to make drawings.” This is proof that certain works make people see the world in a different way.

Bruno Moreschi: Yes, this is precisely one of the great consequences of art. What about this other work, Caminho Isotrópico de Sinceridade Crua [Isotropic Path of Raw Sincerity] (2010)?

Carla Chaim: It’s a video produced last year. It came from an interest in working with the mobile body. I wanted to think of a drawing made with my body in motion. And in this work I began to think of my body blended with the background. If you notice, there’s almost no contrast in the shot. I’m wearing white in front of a white wall. This way, my body also becomes the paper. So, I walk parallel to a wall with an oil crayon. All this in a straight line. The drawing is precisely this path. And once again my body becomes instrument to produce a work of art.

Drawing Lab

By Agnaldo Farias

Text published in the Prêmio Energias na Arte catalogue, Institute Tomie Ohtake, SP, BR, 2009. Carla Chaim won the first prize – Self-directed Residence in The Banff Centre, Canada

…The actual production, feeling confirmed by this small but expressive exhibition reaffirms the idea that nowadays there is no more supremacy of any esthetic trend, breathes the liberty of attempting all forms of expression, including the return to conventional supports, appropriate through surprising angles which demonstrates its power and legitimacy.

… the work “Drawing Laboratory / Specific Sensorial Experiences”, 2009, by Carla Chaim, includes a curious articulation between installation, drawing and performance, and moreover, introducing visual and sound effects.

The parallelepiped statement by a light metal structure where each stem carries a small video screen and headphones, combined with a series of framed drawings displayed on the closest wall.

The scanning of the drawings rapidly brings the conclusion that they are electrocardiograms associated to several activities – eat, sleep, ride a bicycle, walk on a running machine etc, activities which were completed by the artist, recorded and reproduced in sound and image in the screens and headphones installed at the side structure.

Work piece body confounds with the artists body: bringing its presence to the exhibition space.

The material neutralism, due to its technological appearance and the scientific accuracy of the diagrams, contrasts with the sounds, inconsistent rhythms of breathing, and the exhalations proceeding from the effort.

The device installed in the room, the appliances used by the artist, some of them elaborated within the engineering that consist the body as a physical machine, restores other aspects of the human.

As a drawing of itself

At first sight, these images presented by Carla Chaim can make you uncomfortable. That is because of the effort required from the body exhibited in her videos. A priceless effort, you may think; a under exploitation of the body which will serve for nothing more than the drawing plan. Moreover, the drawing indicates a certain inability, an apparent lack of dexterity.

That is because even the body or maybe the body more than anything, has been made as an instrument, which serves today the most immediate purposes. By the logic of the current functionality so much effort should present, like everything else, a much more simply comprehensible result.

Nevertheless, the image of a under exploited body which has limit as its theme, points out the limitations of a fully functional organism. The body, which benefits from all its capabilities; capabilities and skills are what definitely constantly face its limitations, and so they shape it. Seen by its outline and it is full only because it emerges from its limits.

The body presented in these images, on the contrary, experiment the barriers created by the body itself and exhibits the incompetence as a possibility. In conclusion, it shows more evidently its instrument condition when performing its limitations. The image disquiets possibly because it does not show positively the constant instrumental condition that our everyday life has become.

Or what else do these images let us see?

The starting point is the screen, which is also the paper, the support or finally the blank space, being always presented as something to affront, to face. The action starts. The path drew by the elbows makes a pair of wrecked wings, from a broken symmetry of dumbbells. The head lows helping the neck to reach. The shoulder folds in order to make the arm hold. The hand is useless but it remains tense, participating with the other parts in the effort made, as a whole. This was the body defines itself as much as it can which is much more than expected.

A metrical movement makes two forms appear. Unequal, they seem to compete. None of them will win. The drawing curves with the body, making balance. The hand touches the ear, rubs the neck because the spine folds. A dance without a song, with exercise’s breathing: endurance is needed to get you yourself crippled.

How to know when to stop? Where is the point which shows the possible, the enough? Is the body fatigue that starts to show it or the curiosity of the eye, which starts to demand distance?

Every segment of this video works is a short move, a record of an attempt. More its records are seen as attempts more they gain in plight. The attempt is a final form.

Without the image of the previously twisted body, remains to the observer the hint of the limit. His eyes travel the drawing, without showing, however not without an effort. Now testing the place where the body leaves, with an immobility of an observer who does not face closely the paper.

Carla Chaim’s desire to plan and control her movements in the majority of her recent works is clear, as exemplified in videos such as: Certain Moon (2011) and Eclipse (2012). These show us a rigid body used as an instrument for the execution of a meticulously calculated project. In some of her drawing series such as Immortal Process, the Hiccup of Life (2009), Folds (2011-) and Cubes (2012), the body is absent, but the precision of the execution and even the choice of graph paper in the latter grouping reveal and emphasize the importance of the planning that goes into Carla’s work. It is also symptomatic that in all these works, the artist can forfeit her total control over a formal outcome. For example: the way the lines occupy the origami paper is only defined by the necessary folds to “construct” the animal after, which the piece is named. Between totally controlling the aspect of the work and literally following a pre-determined process, she chooses the latter solution, her body once again transformed into a mere drawing machine, devoid of emotion.

The instruments chosen to transform the gestures into drawings contradict and propose the apparent methodology of its making. While using a subtle and precise pencil may seem a logical option, Carla Chaim chooses an oil bar, thick and messy, or a piece of charcoal and as for support, a wall with all its imperfections, a vaguely clumsy corner, or Japanese paper whose transparency is unpredictable and uncontrollable once folded and painted. This way, the edges fray, the lines hesitate and advance fitfully, at times quick and clear, at times indecisive and staggering. The outcome is the finished drawing, which carries the stamps of the challenges of this process. Its beauty originates primarily from the still palpable tension between the purity of the initial idea of the project conceived by the artist (almost always extremely simple, it is worth emphasizing) and the manner in which, while executing the piece, she creates something unexpected: a piece that is complete and happily contaminated by the world.

When inverting the order, where again precision and chance confront each other in Carla Chaim’s work, the drawings from the series: Exercises for the Construction and Fixation of the Infinity (2010-) somehow complement the considerations taken above. Here, the point of departure for creating is randomness: soap and white paint bubbles of various gradations are blown freely over black paper, which thus becomes a deep sky in which the white circles draw stars and galaxies. Once this first step is concluded, the artist invents one or more constellations, joining some of the white circles with traced lines, only this time using a ruler to achieve extreme precision.

Evidently, as mentioned, the reversal relating to the pieces previously described is complete (the drawing is made in white over black, and the planned intervention comes after the more random work), but it is undeniable that the clash we witness remains the same. On the one hand, the beauty of chance, synthesized here by the free gestures, closer to a Jackson Pollock than something automated where the artist distributes the bubbles on the paper. On the other hand, the irresistible temptation of establishing order in chaos, or in considering the mythical origin of the majority of the constellations, transforming drawings into stories.

The body of the material

By Cauê Alves

text published for the exhibition “Pesar do Peso”, Galeria Raquel Arnaud, SP, BR, 2014

Carla Chaim enters directly into a dialogue with the heritage of constructivist and geometric art in Brazil, and is a model to many artists of her generation all over the world. In her work there appears to be an echo of the folded surfaces of Amilcar de Castro and bodily notions such as those fashioned by Hélio Oiticica, Lygia Clark, Lygia Pape and Mira Schendel. Instead of simply carrying on with this salient of historical avant gardes, Carla Chaim reinvents poetic possibilities based both on photographed actions as well as traditional materials, paper and graphite.

As in a non-figurative origami, with two or three folds, a square forms triangles and generates rectangles. Drawing upon simple geometric elements, Carla Chaim’s compositions make the back of the sheet into the front, and vice-versa. Because of its transparency, when the paper is folded, the black form painted on the front goes to the back, yet allowing itself to be seen through the paper in more of a grayish tone. The artist breaks with the opposition between front and back, the white of the paper and black paint, as well as that between a presumed interiority of the material and its outer appearance. In her work there are no oppositions between back and front.

The gesture of folding that diminishes the surface for outer contact is the same one that brings about the joining of planes painted black. At this juncture, the furrow created by the fold is less a line separating one side from another than the possibility of their union. With the paper unfolded, there remains a memory of what was once sheer continuity. Distinct separate forms separated by the tiniest fissures confine themselves on the borders of the square. The line that remains is born from turning one part of a piece of paper over the remainder. The result is not a lacerated plane, but the final composition alludes to a mismatch of forms in relation to a prior painted unity that has since come undone.

Carla Chaim’s paper creations are not satisfied with the plane. As they are folded they take over 3-dimensional space, assuming a corporeal dimension. The series Queda (‘Falling’) – in which part of a roll of paper runs down the wall to the floor – requires another posture from the body of a visitor. The design unfolds from the vertical plane, which presupposes the erect position of the body, and expands into the horizontal, compelling us to lower our head to see it. These works revisit the abandonment of the traditional space of representation, in which painting was analogous to a window, and mingle with the dirt and banality of the world we live in, the place where we set our feet.

The discussion of the notion of corporeality becomes more explicit in the photographs, in which the surface of the artist’s body, on a real scale, emerges partially covered by the same Japanese paper as the other works. But in it the straight lines clearly do not adapt to the artist’s body in motion, and gradually give rise to crumpling. The impossibility of finding a complete synchronicity, a perfect fit between the artist’s body and the folds of paper, results in images in which the movements of her arms and legs are constrained by geometry. But in approaching dance, it is as though the artist had raised to the utmost degree the expressive power that an unfurled rectangular sheet can possibly attain. The conflict between the human body and the body of paper is resolved in the assertion of their shared organic origin.

These photographs, in contrast to the descending movement of the series Queda [‘Falling’], point upwards as they approximate pyramidal structures. In another pair of images in which the artist is leaping, her movements are interrupted not by geometric forms, but by the photographic act which freezes them and reveals to us the weight of her body. The volume and direction of her body on the vertical and horizontal planes are analogous to the black rectangles absorbing light, both floating in the air.

In other photographs, the relationship between the body and geometry is also problematic. Now the body is bending to find a position allowing for a balancing of tiny cubes acting as a support; now the cube itself takes bodily form and becomes a solid encased in a folded paper that partially adapts to its volume. The graphite is both a drawing instrument as well as the raw material for sculpture. The solid chunk of graphite comprises a uniform body both inside and out.

Even so, in this artist’s work, the body is more than a mere support. It is the fundamental catalyst for amplifying the expressive potentials of the material. The paper in her work takes its bodily form as of the moment when it is folded and there is no more opposition between front and back, inside and out. The body is the place where subjectivity and objectivity come together. More than a photographed image, it is the field of feeling and thought, it is what makes possible the artist’s direct experience of the world. It is her body that executes these movements of performance, instigating a clash with its surroundings as it provokes other bodies. Carla Chaim addresses both the body of the material as well as the material of the bodies

Carla Chaim

Museu da República

REMARKABLE OBJECTS

Rio de Janeiro, 2016

Carla Chaim, granted with the Foco Bradesco ArtRio Prize, presents Remarkable Objects at Galeria do Lago, an exhibition showcasing her latest works resulting of her interest on the body, space and movement. Due to its historical and architectural relevance, the Museu da República [Republic’s Museum] and its imposing rooms called the artist from São Paulo’s attention. After hours of research in archives and carefully studying the palace’s plant, she chose to focus on its large chambers, chapel and Getúlio Vargas’s bedroom. Deprived of decorations, ornaments or furniture, the palace’s primal and structural form is emphasized, thus prioritizing its essential shapes. Carla reproduced, in a reduced scale, the voids of these spaces resorting to graphite, a material she often uses in her works. This dark form of carbon, material constitutive of the pencils used to draw maps, blueprints and architectural projects, perfectly suits the purpose of the piece. The various drawings on white or graph paper were conceived in relation to the plants she analysed during her research, and appear as a materialization of a field/space. Straight lines, scratched with graphite, cross the paper forming narrow, sharply directed angles. Fragments of graphite stone, fixed on the surface of paper,confer an intriguing sense of relief to the repetition of lines, almost turning the pieces into sculptures or three-dimen- sional drawings.

The experimentation of space is what characterizes this exhibition. These “projects and exercises”, as Carla Chaim refers to them, highlight the organic dimension of her work. The body turns into an instrument to consider the relations between spaces, movement and art. In fact, the photograph Pesar do Peso registers the dialogue between a body in movement and the static rigidity of the geometrical form. The camera tries to capture a movement, but the totality of the image escapes the focus except for the black rectangle fixed on the wall. It is very clear to perceive the difference between action and stagnation, movement and stillness. The body is an agent, an active character that determines the construction of the piece and underlines its inherent dichotomy.

In the video Espinha de Peixe [Herringbone], recorded in the exhibition space, the artist moves and position her feet according to the patterns of the parquet floor – the so-called herringbone pattern, that thus becomes a parameter of a choreographic composition. Three white walls, the floor and Carla’s steps: her body wanders, with no apparent purpose or destination, but respecting certain limits. If she sometimes seems to seek the edges of the room, when she perceives there is no way to go further, she changes the course of her displacement. As her feet adapt to the oblique lines of the floor, her body tries to renew its balance by seeking other ways and rhythms to pursue her itinerary, that appears as an attempt to appropriate the space. Some excerpts of the recording in rewind reproduction give the impression that the artist is walking backwards. In those moments, the sound is also altered, creating noise and interference. Thus, in many ways, Chaim questions the present-day condition of the subject inserted in a society: its physical and social limits, movement of the body and materials, as well as new possible approaches to art pieces. As the artist herself defines, she doesn’t “ work with(in) a specific medium, rather with(in) a poetic line and discourse” and explores different formats and forms to materialize it.

Remarkable Objects showcases the work of an artist that stimulates both gaze and thought, constantly looking for other strategies to express her immense yet intimate inner creative impulse. If her objects are remarkable, it is because of their singularity, sensitivity and significance.

Carla Chaim

CasaNova Arte

PRESENCE

São Paulo, 2015

At “Presença”, the works produced by Carla Chaim has as a starting point the space where the exhibition takes place. At this show, just like in her previous works, the exhibition venue is approached as the mainly material for the development of artworks that reflects intentions from the act of drawing, taking in granted not just the material aspects but also the space is an instrument for reflection and research about the world.

Originaly created from the architectural elements of Casa Nova, the photos, sculptures and the video “Presença” explore – in a ludic and analitycal way – the space which hosts them. Appropriated by the architectural fragments of the space, the works reshape the enviroment and through displacements and mirroring reorganize a new phys- ical perception.

In the everyday life the perception of the space is usually the city; it’s where the minors places are located (homes, offices, art galleries) and it’s also where life truly unfolds itself. Therefore, the spatial expression of the drawing – on urban layout, on the housing architecture – which defines the place of objects and bodies, proposing their limits and guiding their behaviors.

In Presença, the structural aspect of the drawing is discarded in favor for a negative approach to the gester of drawing. Be it on the body of photographs, in which the body acts in between the empty space; or in the video, where a sort of spatial freehand drawing unfolds and fades in the room; or in the three-dimensional peaces, black copies of either structural, decorative or stylistic elements, the works access the architectural design from its negative of its extructure. As arising from a carrollian concept, the works break down and reflect the real world, creating overlays that seem to be able to fold and unfold the space.

The exposure assembly, bringing together the three-dimensional pieces, photographs and displaying video in the room where it was recorded, enhances the reflexive aspect of these deconstruction and reconstruction operations in space. Through this negative exploration, Carla Chaim reorganizes the enviroment and dismantles its natural- ness: traced from the house, the works reflect and blend again into it, so that, in an unexpected way, the space becomes visible as if the first time.

Carla Chaim

Athena Contemporânea

OIL TAPE CARBON

Rio de Janeiro, 2017

The title of this exhibition by Carla Chaim points to the three central materials of the works presented here; more than that, choosing these words also denotes the relationship between her research and the physicality of things. Consequently, the place that the body of the artist and the body of the spectator occupy in relation to the images is therefore essential.

The artist carries on an investigation into the relationship between architecture and the human body through the act of risking and recording. Her body moves toward the walls of Athena Contemporânea carrying an oil stick in one hand, and she draws the boundaries between what is inside the gallery and what would be outside. An irregular black line runs through the usual white space of the exhibition cube, also highlighted by the white clothing worn by the artist—this is a reminder of the historical equation between graphite and paper. This risk brings to the viewer a notion of boundary that carries within itself the irregularity and instability intrinsic to human anatomy and our gestures. Although the sides of the gallery have symmetry and a geometric plan, when we descend from this Platonic sphere and yield to this vital experience, the straight bold lines quickly become irregular and faded.

Two video cameras record this action, which is projected onto two monitors. Installed back to back, they seem to em- phasize the inability to grasp the whole—whether it is architecture or any other image. The invitation to the body (now of the viewer) follows—to move from here to there, circling the sculpture-videos and trying to accompany an action that has never happened in a separated way. But when it turns into records that resemble a surveillance camera, they also suggest that we watch the movement of the artist’s body. If the act of being drawn in the gallery has recoded its rectilinear space into something irregular, the option of recording with video and showing the action in this way doubles the same space in two and opens Chaim’s experimentation as to the different ways of recoding a same space—not only formally, but also in other semantics.

These elements become even clearer in the series “He Wanted to be a Flag,” presented here for the first time. The artist uses carbon paper, a material she has been exploring recently, and presents it in different compositions. There are different ways to approach this series, but we can begin with the path we have taken of its relation to the gallery’s spatiality: the starting point for the use of carbon is always the floor plan of the space itself. Carbon paper, commonly used to duplicate documents because of its chemical composition, is used here to duplicate the geometry of space. After cutting the paper, different ways of folding and supporting the material are presented and the layout of the gallery is dismantled before our eyes. The relation between body and architecture is again present, but with no need for this dialogue to be pamphletary, approaching the desire of the one who observes—her work, for example, of geometric abstraction.

On the other hand, the title of these works and their spatial configuration offer elements that allow a distant interpreta- tion of theoretical-formal aspects of Western art history, and which lead us to a greater polysemy. We have shapes in front of us that inevitably recall flags—some hung parallel to the wall, while others are laid on the floor. A third group, also placed on the floor, consists of a series of folds that take on the gray tone of the concrete floor as an element of their structure—without adding poles, these two small piles seem the most distant and therefore the most desirous to be flags one day. There is an anti-monumentality in these objects— all of them are more like kites than flags. Their wooden poles, added to their black color and inevitable association to mourning, for example, seem to declare their inadequacy to the grandiose and identifying statement of any flag. Powerful as a formal artistic experimentation and deliberately withdrawn as an inflamed argument, they are at the levels of our feet and it would only take a false step to break them apart.

Finally, one notices that the works gathered here are examples of Carla Chaim’s experimentation and obsession with different ways of exploring an image from a specific architectural space. If drawing and its expanded field of language and poetics are a safe space for its practice, it seems that it is in this exploration of a certain artistic informality—so well represented in these pieces that relate to the ground and the absence of control of gravity—that her research seems to reach a place that intrigues those who accompany this research.

In the same manner that these options take a risk and illustrate the exit from a safe place, the invitation is given that future texts about her work will also amplify the scope of reading that often remain in the dangerous comfort zone of relations with abstraction, geometry, and formalism. Let us learn from her videos and flag projects and ponder that mourning can be anywhere—especially in the silence of black squares—just as the relationships between body and architecture can be less hedonistic and more relative to our physical and territorial limits.

Galeria Raquel Arnaud

THE LITTLE DEATH

São Paulo, 2018

STRUGGLE

When looking at today’s artistic production, a large part of it deals directly with social problems. Artists, curators, galleries, museums, etc. are using “street” language, the grammar of struggle and political engagement which mirrors the militant tone that belongs to (or seems to belong to) everyone. In fact, it could not be otherwise. Brazil’s current scenario is particularly difficult and tense, and the growing threat to citizens’ constitutional rights has brought back to life, old ghosts from the dictatorship we all thought were forever buried. (Marielle Franco, a black, female feminist, and human rights activist from the Maré favela in Rio de Janeiro was executed while I was writing this text). This context, which some have foretold as the worst moment in Brazil’s contemporary history, impresses a sense of urgency on our actions and forces us to adopt an effective stance that goes beyond privileged positions. It makes us identify ourselves collectively amidst the struggle and want to adopt the same grammar of the situation we are fighting against.

However, this feeling of a “common struggle” (together with its related artistic forms) is also what threatens to divide us. As paradoxical as it may seem, our capacity of “emancipation” is not in the convergence on the front, but in the power to associate and dissociate (ourselves), to create sensible ruptures and schisms, i.e. it rests on the possibility to manage “practices of plurality” (Rebecca Solnit) against the “dullness of our political imagination” (V. Safatle).

In light of recent events, the aforementioned contradiction reached me during a conversation I had with Carla Chaim earlier this year. The artist told me about an activity she carried out with a group of artists at Casa do Brasil in Madrid during the last ARCO art fair. Feeling concerned about the current situation in the country, the group organized a public demonstration “since just one exhibition would not make sense “, and they issued a short manifesto. “Action and

Reaction,” was the chosen title, and the event echoed in social media spontaneously.

With this background context, the proposal Carla Chaim now exhibits at the Raquel Arnaud gallery offers answers and poses questions. The set of works of the show “The Little Death”, a suggestive name which is another expression for an orgasm, translates the syncopation of “mourning” and “pleasure” that are part of the dynamics of human desire. In the words of the artist, this is a title where “the end and the ecstasy” converge simultaneously, a heading which is capable of reversing the gravity that binds us to the ground.

Several works of art presented herein continue querying about the questions Carla Chaim has been posing since last year, in particular, when she created “Óleo Fita Carbono” [Carbon Oil Tape] in Rio de Janeiro. Once again, she questions our capacity to imagine through materiality without having to adopt the inflamed apparatus we see on the streets. Contrary to the militant colorfulness we see in some current exhibitions, the tonality here is morose and downcast – nearly monotonous – and makes us feel the uncanny strangeness of a “calm” display in tumultuous times. It is, however, a Brechtian distancing effect which focuses on the spectator’s active ability to adhere and give an opinion without wanting to overwhelm him with the illusory world of narrative. Arranged on fragile rods on the ground floor of the gallery, Chaim’s black flags (from the series “Ele queria ser bandeira” [He wanted to be a flag]) are a good example of this.

The heavy carbon paper, whose shape “duplicates” the gallery’s floor plan, eliminates the irruption of the gesture. The artist seems to ask, “how can we raise flags in times of barbarism?”.

Being close to the “erotic or emotional alternative” (anti-monumental, we could say) that Lucy Lippard, an art critic, mentioned when referring to the 70’s postminimalism artists, Carla Chaim proposes a speculative and provisional itinerary to us that summons the body and the memory into an active perception of these proposals. The fold, a feature in previous works, now yields its relevance to composition through the “sum of different surfaces” where “third bodies” arise from adjacencies and juxtapositions. A subtle, material evidence is offered to the public especially on the ground floor of the gallery in works of art such as “Gruta” [Grotto]: four large drawings made with oil stick that are nearly 3 meters high; “Ar- raias” [Stingrays] and “Dois” [Two], two series that explore compositions with different types of paper; “Corte Inversão Movimento” [Cut Reversal Movement], a (de)composition of books from a study of geometric forms as contained inside them (a “mise-en-abyme” of the referent); “Line Pieces”, parts of an action in which the body “creates a fiction” out of angles, corners, sections; and finally “Luto_luta” [Mourning_Struggle], a poster by Verena Smit, an artist who is known for developing precise work about the ambiguity of language, and whom Carla Chaim invited to join in this exhibition.

But I think one single work of art on the upper floor is capable of speaking up for the whole exhibition and embracing the struggle (and mourning) to which I refer since the beginning of this text. Entitled “Somatu”, the video installation displays a continuous fair- play between bodies, thus summoning contemplation and action, distance and closeness, the optic and the haptic. Its arrangement across the entire length of the room forces us to adopt a certain point of view which, in addition to the mesmerizing movement of the action on the screen, creates a retreat from language, some sort of an opening to a new organization of the sensitive. Invested with a dense materiality that is not looking for genres or identities (it is difficult to identify if they are people, animals or amoebas), three bodies are entwined in some sort of “mating dance” which tells us about another kind of movement that disagrees from what is contemporary and urban. Here “the artist reconsiders the innermost part of the body, the physical, internal and individual sensations recreated by the experiences of the world. A world of mourning, but also, a world of transformation and pleasure. “

Without intersecting with the aesthetics of the urgency we see around us, Carla Chaim’s exhibition offers us the entire lexicon she has developed in recent years and even expands our imagination regarding the other uses of space, which are more affective and less prone to surveillance.

Carla Chaim’s North consists in an inquiry on the discipline of drawing, a technique that she has been continuously challenging, always seeking to defy, expand, and unfold its principles. With this purpose, the artist uses one of the most prosaic and universal tools employed for drawing, namely the graphite, which inherited the Greek etymology related to the act of writing or drawing. If indeed the artist’s work can be included in the field of the graphic arts, one might say, nonetheless, that she draws in negative, as her intervention is structured around an inversion of some of the main conventions of the discipline, but also around a mirrored dialog with the exhibition space.

Firstly, despite the fact that until now the practice of drawing is associated to the act of delineating a surface with a tool, usually a pencil, in North the graphite is not used to trace lines or outline shapes, but rather it is reduced to powder and spread out in a rectangle shape that doubles the measurements of the room. In this case, the graphite ceases to be a tool in order to exist as pure materiality occupying and filling a given surface.

Formally, the strict geometry of the dense black graphite extension appears as a counterpoint in the space it occupies, the green room of the Pombal Palace. In fact, the rococó sensibility attested in the profusion of wavy colored ornaments that adorn the walls and ceiling of the room contrasts with the austerity and almost minimalist aesthetics of the graphite rectangle that covers a considerable part of the floor.

Carla Chaim’s drawing-installation also contradicts the drawing that structures the exhibition space itself, as it also diverts from the guidelines that sustain its architectural plant. Through the simple gesture of dislocating the graphite rectangle from the axis of the room, the black surface seems to stand out even more from its surrounding context, sustaining and reinforcing the contrasts already mentioned above.

Thus, one might say that North is a particularly auto-reflexive work regarding the practice of drawing in Carla Chaim’s research: not only by experimenting with the graphic arts’ emblematic tool and surpassing the limits of a bidimensional surface, but also by confronting the underlying norms of the architectural design of the colonial building of the Pombal Palace, and all its reminiscences of an ornament tradition.

Through these contrapositions, Carla Chaim’s intervention destabilizes perception, misleads the experience that the spectator can have of the exhibition space, inviting him to consider it under a new angle. The visual polarities triggered by the installation may open up new horizons to the understanding of wider geographic and historic polarities.

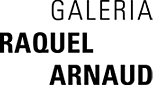

FEVER

“(…) In the gesture, each body, once free from its voluntary relation with a function, whether if it is organic or social, can for the first time, explore, inquire and show all the possibilities of what it is capable.”

Giorgio Agamben

Whoever is expecting to find shelter in this architecture is mistaken. At first, there is a box inside another box; a wooden grid at the center of the gallery. A hollow structure invites us to contemplate suspended drawings, to walk in and out, front and back. Everything seems to be in its place, until we approach the works. Therefore, the apparent rigidity of the space meets the manifestations of a restless, feverish body. Our eyes run through vigorous and repetitive lines, material densities, scratches, slaps, explosions and shards: no traces of consolation, no redemption.

Fever is an exhibition that rounds the reflexive powers of gesture. Free from any functionality, Carla Chaim’s actions explore the rebellions and uprisings that fit into one body. While the artist is usually identified by her concise palette, centered around black and white – a choice that fulfills the role of maintaining the production linked to its fundamental operations, stripped of accessories –, here we see a strong interest in red and its variations, a result of the search for a new radicalism and a widening of subjective contours. However, it is not about understanding her gesture as an expressionist fetish, a way in which we would have been summoned to look for traces of psychological singularity in her production. In addition, it is not our duty to identify, in her scribbles, an author’s mark that relates to the ideas of style, personality and distinction; the idea of gesture as signature, for example. On the contrary: the lines we see here pursue a certain deterritorialization. They do not document the biography of an individual, but the tremors and vibrations that run through their body, the energy of its movements repeated to exhaustion, such as the visual exclamations that may also be shared at a collective level – since the show has been produced in the past two years, it is possible to say that it somewhat corresponds to the social stress to which we have been submitted.

In almost all the artworks here, such body is manifested by its evidential aspect; in other words, it announces a presence that is constituted through absence. They are scar-drawings that point to the perspective that a body is not made only of flesh and bones, nor only of matter. It is a mixture of wandering machine and instrument, prosthesis and experimentation lab – a battlefield per excellence. The body of Fever is an incorporated body. Two exceptions, however, are “Mão dormindo” [“Hand sleeping”] (2021) and “Conversa-Acordo” [“Conversation-Agreement”] (2021),

videos in which the hands acquire their own animality, as if they existed independently from the rest of the body. In the first one, minimal gestures of the resting member make us imagine that they take place right after the execution of the works: this hand is exhausted from producing. In the second one, an intimate conversation between the hands (sometimes indicating a conflict, sometimes a game of seduction) divides the body of the same individual. According to the artist herself, “when two hands touch, which one is touched and which one touches? Who is subject and object in the scene?”.

The duality that is present in “Conversa-Acordo” [“Conversation-Agreement”] is also visible in other moments of the show. The carbon sheets of paper scratched by nails display mirrored poles

– positive and negative, matrix and copy – recognizing themselves as another being. The same is true for the “embroidered” scratched simultaneously by left and right hands, producing heterogeneous stains that hardly conciliate (in such cases, the wrath is more restrained and focused, in a choreographed rhythmic gradation). The dual other acts as a dialectical solution that disorients and disturbs the alleged reason of the procedure, something that becomes even more intensified by repetition and insistence. Far from reflecting any standardization, Chaim’s persistent gestures distance themselves from the idea of a possible program’s success and efficiency towards an affirmation of the cruelty of failure. Fault is situated as refusal, imposture and impossibility, but also as a constructive way out and an inventive resource. Repeating, in this case, is a way to shred the gesture until it is possible to finally see it and grab it.

There is also a ceramic and graphite set that seems to migrate the lines we see in Japanese paper into the tridimensionality of the space. They are equally irregular lines that suggest organic fragments, which are twisted and reduced to their essence. Such as in the artist’s earlier pieces, graphite ceases to be the means by which something is expressed and starts being an end in itself, a matter of autonomous interest. In addition, some of the pieces with pronounced curves allude to the shape of Louise Bourgeois’s hysterical body, bringing shape and symptom closer.

Finally, I see this Fever that Chaim is showing us as a type of reaction to the state of numbness that strikes us at the moment. Here, immersed in the delirium of the high temperatures, we are summoned to recover the language of gestures, seeking to perform and act on our life drive. Some fever will be there, yes, so that we do not subject ourselves to the uninterrupted failure of the now. Some fever will be there, yes, to guarantee the insurrection of our dreams.

Pollyana Quintella

Wave Collapse

The titles of the installation Colapso de onda [Wave Collapse] (a term taken from the experimental observation of electrons that travel sometimes as particles, sometimes as waves) and of the object-book Multiverso [Multiverse] (a term that denotes the hypothesis of the coexistence of multiple universes) were appropriated from quantum physics, by Carla Chaim, to empower the poetic correlation between the only two artworks featured in this show.

The most evident of the two replicates the rectangle formed by the floor of the exhibition room, with proportions identical to it, excluding the area of the corridor extending between the room’s only two doorways. Displaced 5° in relation to the center of the gallery, the rectangle derived from this twisting is configured by a homogeneous covering of powdered graphite. The material from which it is made refers to the poetic core of Carla’s production: the expansion (or overflowing) of drawing into other media and supports (videos, installations, architecture) outside of those to which it was confined for millennia.

Thanks to the above-mentioned angular decentering, the area embodied by the patch of graphite (which, as a site-specific artwork, briefly transforms the nature of the CCBB’s architecture and exhibition space) simultaneously demands the visitor’s effective physical displacement into the artwork’s interior, thus giving rise to a third level of displacement, now in the sphere of the production of subjectivity: that of the conventional observer, previously restricted to the spiritual appreciation of contemplation, is shifted to another level, open to participation in experiences that are more open-ended, and therefore also marked by a continuous border-crossing between the tangible-corporeal and the intellectual realms.

The show is capped off by the artwork-book Multiverso whose intimist scale contrasts with the largeness of the room-penetrable. Despite the difference in scale, however, the border-crossing operated by the installation is repeated from another standpoint in Multiverso. Produced by the folding of pages and by the subsequent application of graphite powder between them, upon being handled the book also gives rise to experimental situations, insofar as it continuously re- creates drawings and compositions in multiple spaces whose definitive conclusion is marked by the printing of a book especially conceived by the artist as a work that complements the questions that drive this project. According to the artist herself, “each page winds up containing all the others, which I relate with all the ‘universes’ of the multiverse embodied in Multiverse.

Finally, it is good to discard strictly formal readings of Carla’s work, favored by the geometricization seen in part of her work. The main thrust of the artist’s projects is not formal invention, but rather the spatial formulation of fields of experience. In the book The art-architecture complex, Hal Foster proposes the following reading of the main unfoldings of the “dialectic of postwar art.” For that author, that dialectic “produced not only a shift of pictorial illusion into the real space, but also a remodeling of space as an illusion in the broad sense, with important ramifications for architecture as well. […] This book was written in support of practices that insist on the sensuous particularity of experience in the here-and-now and which resist the stunned subjectivity and the arrested sociality supported by spectacle.”

(pp. 12 and 13, translated here from the Portuguese)

This observation also serves as a possible backdrop to Carla Chaim’s work. That of the poetics of resistance to the spectacularization that pervades the logic of the market.

Fernando Cocchiarale