Daniel Feingold

jan 31 - mar 15_2014

Often, when faced with a painting by Daniel Feingold, my first question is: How does it start? What is the source – visual or otherwise – of reference? This has been the case since my first contact with Feingold’s work, nearly fifteen years ago. Feingold is always patient, giving my question a moment’s thought before answering. This is the nature of the artist, the way he faces his issues as a painter. It’s a relief to me, especially in New York, where words are spoken as if they’ve been rehearsed. After a while, they all seem to sound the same. They all disperse in the same conformist atmosphere – the same words, the same language, as if talking about painting were the same as sending an e-mail or an incidental text message. Language is soon transmuted into rhetoric without spirit or memory. In this respect, Feingold is clearly different.

When Feingold speaks, he seems to be possessed by a kind of Kierkegaardian doubt, implying that each painting has its own origin despite its close visual coherence with other related works. Few painters I can compare to Feingold, and they tend to be historical artists. For example, I can imagine listening to Barnett Newman, or even Pollock (an artist Feingold has always deeply admired), who, in my opinion, expressed a similar sense of doubt. Regardless of years of practice, the experiences and tribulations to compose a substantial painting have always taken time, and therefore the language spoken in relation to painting as well. The beginning is a matter of working with both time and space. It may seem that Feingold is reluctant to withdraw from the time instilled in his paintings. Although they seem static, they are not. Time is embedded in them like form on a surface. Discovering time in a painting is a perpetual, continuous process. Generally speaking, I’m not sure whether it makes any difference whether a picture is figurative or abstract. Working with time in your favor, following along with it in the act of painting, is a gift. Ideally, this is how the painting should come to pass. I assume that Feingold has his own language to express this idea. The first thought about a painting or about a painting is, in a concrete sense, its true beginning.

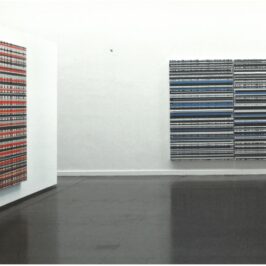

As his photographs are more recent and use an empirical or identifiable object in the external visual world, I am less inclined to inquire about sources. In this respect, painting and photography differ. In the case of Feingold’s painting, the source evolves from within and perhaps indirectly from an expressionist point of view. I refer to the Yahweh series. Although the process involved in composing his paintings is automatic (to a certain extent), as soon as the viscosity of the black enamel pigment begins to decrease, the paint flows out in a series of lines. This is possible because the surface of the screen’s terbrim is slightly inclined in relation to the wall. The pigment volume in each paint application appears to be relatively consistent. Sometimes the volume covers half or a third of the area to the lower edge, while at other times it almost reaches the lower edge, though not quite. This process ironically recalls Mondrian’s proto-concrete, neoplastic-concrete paintings, who clearly discerned the importance of the line not reaching the edge, but often almost reaching it. For Mondrian, this allowed a certain mobility in space, as the eye moved between planes, from one to another, without interruption.

In the paintings of Feingold’s Yahweh series (2013), the reference to the vitality of the paint application, in contrast to the hard-edge style of the Dutch artist, is significant. Despite Feingold’s formidable control over how discrete areas of black enamel are applied to the terbrim surface, the calculated process ultimately lends itself to an expressionist aesthetic. Feingold’s choice of the “God” of the Jews as the title of his series suggests more than a strictly formal process. The way in which the ink flows and becomes a kind of writing or writing (écriture) is not without meaning. On the contrary, it is the true essence that the artist has been trying to obtain, as if the relative randomness of the enamel action were part of a random plan or system, a universe constructed by a creative impulse, indicating a kind of mirror or reflection on the meaning. of the creative act. In this sense, Feingold approaches Newman’s concept of the “zip” within the pictorial field as a symbol of divine light or intervention of God’s presence in Judeo-Christian history. At the same moment, the rhythmic application of paint takes place, referring to what Pollock used to say about the need to be inside the painting. This is also reflected in Feingold’s need to be congruent with time, as when some aspect of a painting begins to fade and form before your eyes.

Once the black enamel reaches its surface stasis and hardens, the panel no longer remains in an upright position. Instead, the artist places it in a horizontal position, lining it up with a second panel to create a diptych. And it is then – and only then – that the expressionist point of view begins to emerge. Before that, the work is just a panel painted black that requires a second panel to find its resolution. It is questionable whether the Renaissance term “diptych” is appropriate here. For the most part, a diptych was usually designed for the exterior of an altarpiece and included a different theme (a different saint) on each panel. While each theme was different, both were dependent on a single theme involving Christian mythology. In Feingold’s Yahweh series, the two panels come together to form “a third voice,” so to speak. Here, the reference to Newman is of interest, in particular his work Onement (Unicity, 1948) in which a red-orange expressionist brushstroke runs vertically down the center of a brown field. In this case, instead of separating the painting into two halves, the vertical red line activates the space and thus affirmatively unites the picture. Similarly, when Feingold brings the two horizontal panels together into a single painting, the work gains an activated sense of “oneness” and thus reiterates the Old Testament scripture about God as a singular and all-powerful deity.

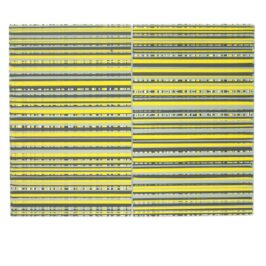

Compared to the Yahweh series, the paintings in the Structure series, also from 2013, admit a similar approach to painting, focusing on the grid and therefore moving away from any allusion to expressionism. Rather than run-off from organic stains, as in the Yahweh series, the paintings are made up of highly controlled, singular ink-spiking events, suggesting a more compact version of Mondrian. Rather than moving linearly in a single direction, Feingold’s squiggly lines crisscross, using colors—especially primaries—that give the surface a more lush, yet restrained, appearance. They are incredible paintings, not only in their execution, but also in every detail of their appearance. They are original, vital and circumspect, to the point that we can explore the complexity of their evolution over time. Feingold dominates every inch of its surfaces without giving up total control. It further allows accidents to produce a painterly effect and thus aligns with a kind of postmodern recycling of earlier forms of abstraction or concretion placed unequivocally in the present.

And the photographs? Where are they located in Feingold’s work? I would say that trees also have to do with space and, in this sense, they have to do with painting. I believe that the fact that they refer to the arrangement of space is consistent with the way Feingold deals with the photo, in terms of how he frames the natural subject within the limits of the canvas. His photos are naturally calligraphic, which we could understand as consistent with the current set of paintings. Whether in painting or photography, Feingold’s work has always been calligraphic in the aforementioned sense of writing. His work is a persistent search for a systemic party. It is a kind of pictorial writing, a condensation of words that invoke his painter’s conscience. What I see in these trees, presented singly or in sets of two or three, is that they play with space. They are looking for a placement. They seek to frame this natural calligraphy in a space, in geometry without angst, without ossification, making it as vital as the dripping paintings in which its fantastic control is forever manifest. Photography, for Feingold, is simply another tool by which painting is discovered. In this sense, his photos offer a necessary complement to his point of reference in this exhibition – the placement of space and the permanence of time as essential to the act of painting.

Robert C. Morgan