waltercio caldas_the state of things

Download the catalog by, clicking here:

political art and the politics of art

In current times, it is not unexpected that politics contaminates art more than any variant of the virus during the pandemic. There are plenty of reasons for this – ethnic ones, gender ones, fascism around the world and many others. The history of art is full of great examples of political art: The death of Marat, 1793, by David; Liberty leading the people, 1830, by Delacroix; and, before that, The raft of the Medusa, 1818-1819, by Géricault, in which, for the first time, a group of anonymous characters, castaway sailors, is portrayed in the high sea on a canvas usually reserved for important historical events, battles, coronations of monarchs and others. It measures 491 by 716 centimeters. The artist became aware of the shipwreck through an article in the newspaper two years before painting, a fait divers. When the survivors arrived on land, they narrated their adversities – they had even eaten the meat of the body of their dead shipmates –, and Géricault got motivated. Guernica, 1937, by Picasso, remains as the most elevated moment of political art in the 20th century. But none of these artworks would be in the history of art for their external political motivations; they are there because, each in their own way, they have contributed to modifying the language of art in their time: the politics of art.

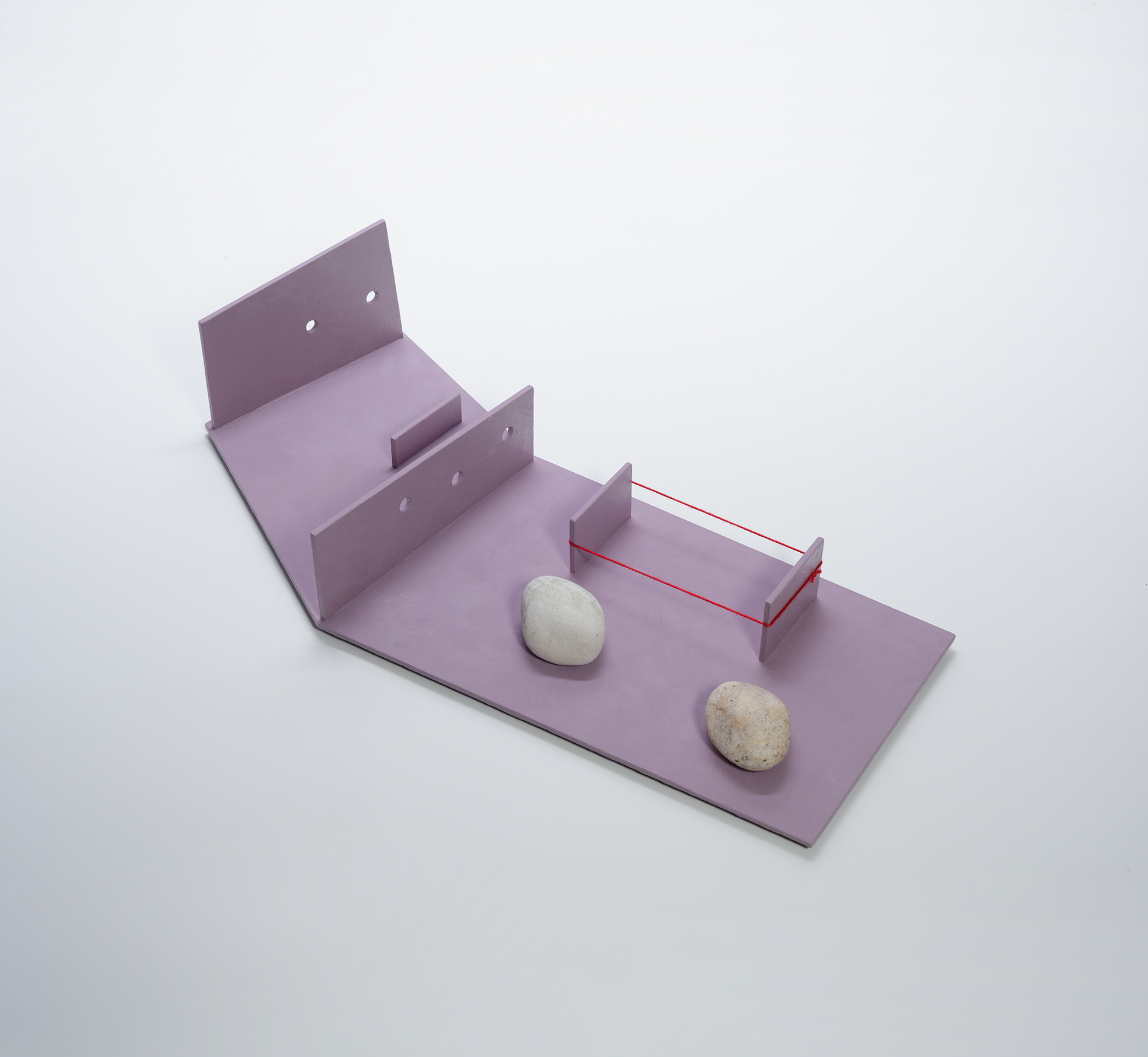

The exhibition The State of Things, by Waltercio Caldas, has numerous examples of political experiences in works with unprecedented experiments in the artist’s long trajectory. And there are many surprises. The way he combines painting and sculpture in the same piece is one of them. There is a game which is guided by language, the only strictly artistic politics that can be practiced within the work of art: the transformation of language, the kind of politics that is not present in parks or protests, but that cries out for new perception experiences.

Let’s examine three of such demonstrations.

Observe Mondrian em casa. Two reproductions of Mondrian on paper are displayed before our eyes, in different dimensions. Depending on the distance we take, looking at the piece requires a certain squint; the distance that separates them dilates the space by its simple presence. The intervention of the stretched elastic piece brings a subtle irony. Between the end of 1919 and the beginning of 1920, Mondrian started his grids, always orthogonal ones. The elastic piece traces a diagonal line, in addition to the curve that outlines the volume of the glass. Always subtle and rigorous, these transgressions and transformations in relation to the work that is present in the title teach us: there is no politics of art without experiences of language.

Contemporary art does not exist without being experimental. We have known this since Adorno and his Aesthetic Theory. But there is something beyond experimentalism in Waltercio Caldas: an asceticism that should not be mistaken for that of Minimal Art; it is an economy that is not averse to the semantic field, to polysemy. That stimulates the experience of the work.

In Acústica II, an exercise about black dominates the scene, despite the subtle presence of red and yellow. Again, for those who have a memory, the history of art infiltrates itself. How can we not remember the Black square, 1916, by Malevich, the years of black paintings by Ad Reinhardt, and, on the left canvas, Soulages? For this artwork, like all the other ones in this exhibition, it is necessary to stop seeing allegories in the traditional sense of the term. There are no images substituting narratives. There is, however, an association of ideas, but not a Freudian one – not the free association of the psychoanalytic situation. Here, the associations of ideas are induced by the works with the possibility of multiplying senses in the subjective apprehension of their meanings.

Caravaggio can serve as a synthesis of everything said above. There is no reference to the troubled life of the artist who gives the work its title. We know of his duels, his multiple arrests, his exile, his short life – he died of a controversial death at the age of 38. None of this is present in this exhibition’s Caravaggio, which is certainly not an allegory. What matters is that the pioneer artist of what would later become the Baroque is in the history of art not because of these facts, but because he dominated the chiaroscuro like no other before him. That is the one whose name is sculpturally written in the painting-sculpture by Waltercio Caldas. The exercises in both paintings – the bigger dark green one and the smaller dark red one –, even though they have different dimensions, are similar: they enunciate two regions separated by a curve. The regions are deftly distinguished, the darker red and green move towards a portion that is only slightly, slightly lighter. Observe that the green, the bigger one, is painted over a canvas which is a lot less thick than the smaller one, the red. But the paintings dialogue with the other sculptural elements. There are golden elements that interfere with the vision of the green painting and leave the red one free, and at the same time build deepness, establish a physical limit of approximation. Let’s review Caravaggio in another way, from now on. We have among us our own contemporary Caravaggio way of thinking.

This is the politics of art, different from political art.

Paulo Sergio Duarte, abril de 2022.

Exhibition: The state of things

From may 2 to june 18 2022

Telephone 11. 3083-6322, e-mail info@raquelarnaud.com

Galeria Raquel Arnaud

Rua Fidalga, 125 – Vila Madalena – telephone: +55 11 3083-6322

exhibitions images